Normcore Was Always a Misunderstood Fantasy

Ten years after coining the era-defining sensibility, three K-HOLE members reflect on normcore’s evolution—and the state of viral trend forecasting.

You had to be there: In the early 2010s, when the hipster choke hold on American culture was still skinny-jeans tight, a group of twentysomething New York creatives started noodling around outside of office hours and formed an artistic collective called K-HOLE. They began publishing PDFs online (and, at least once, on Livestrong-esque rubber bracelet USBs) in the style of prim corporate trend forecasts, presenting brand case studies and coining terms like “fragMOREtation” to describe the cultural phenomena they observed in post-recession New York.

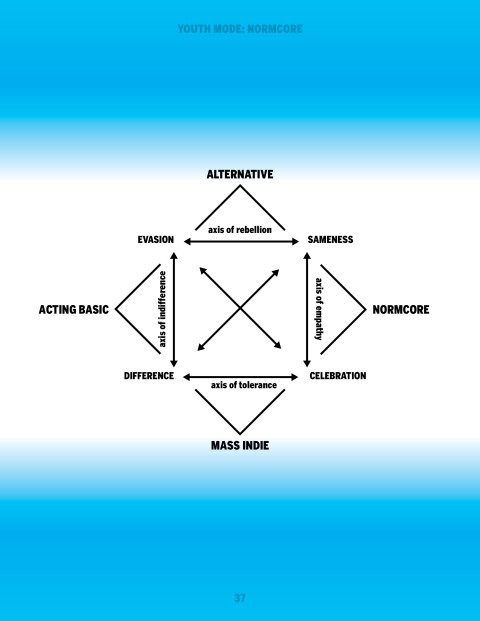

In 2013, K-HOLE published a report titled “Youth Mode: A Report on Freedom,” which dug into the era’s anxieties about maintaining identity amidst “mass indie times,” where one’s predilection in everything from vinyl records to IPAs had become a matter of personal honor. This form of coolness had become limiting, and the collective was preoccupied with the question of what came next—or as K-HOLE member Emily Segal recalls, “How do we free ourselves from the prison that is our own taste?”In “Youth Mode,” K-HOLE defined two ways society would respond to this competitive itch to out-niche one another. One was “acting basic”—you could embrace sameness and lean into the cargo shorts of it all. The other response was epitomized by a deliciously rhymey neologism (originally taken from a punch line in a comic strip) called “normcore,” which K-HOLE used to describe a slippery philosophy to adopt based on ambiguity and code-switching between social situations. For a while, the PDF circulated amongst the usual insidery downtown art scenesters, and it might have stayed that way had New York magazine not picked up the scent.Thanks to the resulting story, published a few months later in February 2014, normcore—which the magazine described as “fashion for those who realize they’re one in 7 billion”—hit the water supply. “Normcore,” the K-HOLE concept, became normcore, a handy catchall term for describing a burgeoning, semi-ironic style of wearing “ardently ordinary clothes.” Normcore was dad jeans, New Balances, Patagonia fleeces, tube socks in Birkenstocks, Jerry Seinfeld, a regular degular baseball cap, a romantic hybrid of real and imagined suburban Americana. “It was fetishizing this casualization of culture, almost equivalent to the kids in the ’50s wearing denim jeans that were made for farmers and making it ‘fashion,’” fashion writer Lauren Sherman recalls. In a 2014 story for , Sherman pointed out the irony: for most people, dressing plainly, like a Midwestern mom, might just. . . make you look like a Midwestern mom. Could anyone really call dressing “normal” a ?

You couldn’t have invented a better psyop. Aided by the viral cultural machinery of the mid-2010s internet, normcore took over the discourse, tumbling from the mouths of quizzical late-night hosts and gently confused dads alike. Oxford Dictionary even added “normcore” to its short list for 2014’s word of the year (but “vape” won lol). Since then, a concept that once felt potentially sharp and incisive has only further dulled down into a hermeneutics for buying ’90s-inflected basics; you can even see its influence on our current fascination with “quiet luxury,” which, as Sherman points out, does most of its imitators zero favors. (“I think this idea of having good taste has resulted in people having no taste.”)But normcore’s true legacy is most apparent not in our modern New Balance-ification of style but in its status as a cultural artifact that changed the way we identified, defined, and talked about trends and aesthetics today. Coining a sticky name—whether the trend actually exists or not—and thereby speaking an entire cultural discourse into being might have been a novel event in 2014, but these days, it’s just another week on #corecore TikTok; the dividing line between naming the thing and making it a thing has never been blurrier—and the social and real currency of the skill has never been more valuable.To reappraise this moment a decade later, SSENSE spoke to three original K-HOLE members—Segal, Dena Yago, and Greg Fong—about the concept of normcore, its rampant misappropriation, and the current state of amateur and professional trend forecasting.

“Youth Mode,” the PDF report that started it all, came out in 2013. What do you remember about K-HOLE’s original vision for normcore?Normcore was supposed to be an anti-aesthetic?And then the magazine story made it purely about fashion.

GF: Every consumer experience in the early 2010s was obsessed with authenticity. For us, normcore was born out of thinking about the end state. How far does authenticity go? Where does it become taxing? What are some strategies for opting out?DY: Everybody was talking about millennials as being these special snowflakes, and we were thinking about the crisis around individuality in the face of mass appropriation of the Williamsburg aesthetic—that was what we were defining as “mass indie.” We were looking at what the counter to that would be, which was “acting basic.” That was Uniqlo, Nike Free, trying to fly under the radar, corporate office drag. And what ended up becoming the normcore style trend. What we were defining as “normcore” was more about contextualization and belonging. It inherently did not have an aesthetic because it was about trying to respond to or belong to any situation as needed.DY: Exactly. It was anti-aesthetic, but the term we were describing was meant to encompass anything from going to a football game to going to Berghain. It was more about code-switching so that you could feel like you were a part of some conversation rather than privileging individuality.ES: It’s not like it had nothing to do with getting dressed, it just wasn’t only about getting dressed. We were fascinated by the character Cayce Pollard, from William Gibson’s book , who strips the branding and logos off her clothes.ES: I really underestimated the significance of this article when it was in the works. I was just like, like, oh cool, a blog post on . When Fiona [Duncan] got back to me and said the editors were taking it in this very fashion-centric, street style type of direction, I was like, well, that’s weird, but whatever. Maybe it’s OK to just let people interpret this as they will.The article made normcore about trying to dress as boring and normal as possible, but that was just one idea of what “generic” was. In our report, we were like, “it’s important to recognize that there’s no such thing as normal.” It had to do with what was normal in a given context, which is always different. It had to do with fetishizing normality and seeing normality as something that was often rejected in this niche-obsessed indie hipster alternative paradigm. So when you make it about dressing like the ’90s, it kind of is not the point, because that may look normal or generic or touristy in a particular context but not in another context, obviously.

That story was such a bombshell in 2014—almost immediately, normcore went viral. What was that like?Do you wish you had?If it happened now, you’d all be TikTok star

ES: I worked in this building on Varick Street, and there was this big magazine shop downstairs. I remember going and buying the magazine and thinking it was cute because it said “normcore” on the cover. The day that it came out online, it already was quite nuts. There were already tons of journalists, boldface names and even some celebs early on—Diplo was quite an early normcore responder. We also started getting commercial interest quite quickly within the next week; Comme des Garçons reached out to us, Nike, Samsung—all these people wanted to meet, which was exciting and intimidating. We had some professional experience in this world, but in terms of K-HOLE itself, it was like a nonhierarchical zine started by friends when we were all 22 and 23. We were not really prepared to become a functioning small business.GF: We were very sincere in our approach, but we knew that we were doing something that this British writer, Huw Lemmey, described as writing in the “lexicon of dickheads.” That was kind of true. We were imitating some form of language but doing it from this truly personal point of view as downtown New Yorkers in the early 2010s. To go from this thing that felt very insular to something that Jimmy Kimmel is making a joke about—it was so crazy.ES: It was hard to know if it was important for us to set the record straight or if it was better to let the conversation play out, because part of what we wanted to do was feed things into culture and see where they went. We didn’t feel super strongly about policing the meaning of what we wrote.ES: No. We had a relatively sophisticated vision for what we were trying to do with K-HOLE, and I was really worried that it was all kind of reduced to this corny meme. I wish I hadn’t been so worried about that. But it was definitely overwhelming to know what to do when your very indie group project gets international mass media attention that goes on and on. It’s ten years later, and I get dozens of Google alerts every month for it.DY: Ultimately, what was most interesting for me was seeing the way that it had legs and seeing how little control we had. What I learned from normcore was how information flows on the internet and how things get taken up by different people who want to have a stake in the ground.GF: It’s hard for me to imagine doing it today, where we’d have to be like, “OK, guys, what’s our Instagram promo going to be?” That already makes me feel burnt out.

Even though the fashion interpretation of normcore doesn’t quite embody normcore’s original meaning, we see its influence everywhere today—in gorpcore, Zizmorcore, the whole stealth wealth/quiet luxury thing. People still crave a kind of everyman ambiguity. Could we say that normcore’s appeal is how it offers a way of bulletproofing oneself from the trend cycles—things like cottagecore or mob wife aesthetic or whatever Gen Z is doing?All three of you still work in the consulting or trend forecasting space to varying degrees. What do you make of the state of trend forecasting? Remember how everyone was making their “in/out lists” at the end of 2023 for New Year’s Eve? What was that all about?

ES: Yes, definitely. For us, rather than being about tiny micro trends, the thing that we were trying to bulletproof against was the of specific hipster identity. And now there’s a much more rapid trend cycle, and it is about keeping up with things.GF: But especially for younger Gen Z, I really do think that they embody normcore the way that we meant it as a philosophy. There’s an adorable clickbait YouTube video where it’s a bunch of young Zoomers and millennials rating each other’s style. The millennials have no idea what is going on with the Gen Z kids, who are all dressed like characters, and the Gen Z kids think the millennials look “like NPCs.” They actually use that word. I think Gen Z, at the very least, embraces clothes a little bit more as a costume, and that’s what we meant when we defined “normcore.” It was born out of this desire to seek relief from being pigeonholed. Things become “aesthetic” in scare quotes.DY: In the last ten years, pattern recognition has become a cultural activity. You see that on the bad end, like QAnon, and on the more fun end with the pervasiveness of trend forecasting. When we started K-HOLE, we chose that format because it was an interesting way to do cultural criticism using language that was accessible and circulatable. But I think that’s now become the cultural norm. That’s how we connect with one another, just coming up with these theories.

What is a trend really but a low-stakes conspiracy theory? I never thought of it that way.Is it clear to you when a trend forecast is coming from amateurs versus the professionals?

ES: There’s both genius trend forecasting coming from spontaneous sharing online, and there’s this blurriness that comes with it, where anything can be named as a trend. There was this whole thing last year where “red” was a trend on TikTok, and I was like, ?ES: I mean, no. I think an amateur and a professional have kind of an equal chance at hitting the nail on the head. True flashes of cultural insight happen where you’re lucky enough to just put the right words against the cultural phenomenon at the right moment. It’s like when there’s an amazing song lyric that just sums something up so perfectly.

K-HOLE’s follow-up to “Youth Mode” was a report titled “Chaos Magic,” which seems like it foresaw the current obsession with “manifesting.” Was there anything you look back on now that you think, ah, we didn’t get that one right?

GF: The “Chaos Magic” report, for me, is the weirdest one, because it was also created against this backdrop of K-HOLE falling apart as an organization. Our East Coast liberal arts and arts educations were pushing us to distribute elsewhere. It felt like this come-to-Jesus moment. Everyone felt so distant from each other, and this was the only thing we could figure out how to articulate together in a way.ES: We got a lot of things. I think we always wanted to do a report on parenting, way before any of us were even close to being parents, which I think would’ve been really interesting. But we weren’t really trying to make super specific predictions that were going to come true or not. We were just trying to reflect back the stuff that we saw in our world and then extrapolate from there. That’s still true for trend forecasting a lot of the time. There are seeds of the future in the present, and there are patterns that might be weak signals now, but if you can put the pieces together, you might be able to get a sense of what’s coming.We did a private report that had to do with the future of men’s style for a more commercial setting, and we were really certain that men’s nail art was going to become a huge thing, which it kind of did, but years and years and years later. When we finally started seeing more of it, we were like, “Yes, we got it.” For us, there wasn’t a huge difference between a trend and an inside joke.

Now Open: The Ice Cream Shop The ultimate summer surprise. Introducing the Ice Cream Shop, a new limited-edition collection of the Miller Sandal and Ella Bio tote in colors inspired by classic ice cream flavors. The iconic Miller sandal is available in eight colors: Rainbow Sprinkles, Neapolitan, Orange Sherbet, Strawberry Swirl, Lemon Ice, Strawberries N’ Cream plus Pralines N’ Cream, Tory’s favorite and an exclusive to toryburch.com. The Ella Bio is available in sorbet pastels, along with new matching small leather goods. The Ice Cream Shop collection is only available this summer.

Now Open: The Ice Cream Shop The ultimate summer surprise. Introducing the Ice Cream Shop, a new limited-edition collection of the Miller Sandal and Ella Bio tote in colors inspired by classic ice cream flavors. The iconic Miller sandal is available in eight colors: Rainbow Sprinkles, Neapolitan, Orange Sherbet, Strawberry Swirl, Lemon Ice, Strawberries N’ Cream plus Pralines N’ Cream, Tory’s favorite and an exclusive to toryburch.com. The Ella Bio is available in sorbet pastels, along with new matching small leather goods. The Ice Cream Shop collection is only available this summer.